Erik Bauer captured reactions. By day, he was a research chemist for Kennametal in Pennsylvania’s Westmoreland County, a region of dusky mountains and dense forest; but when the sun went down and Erik had finished observing how chemicals best reacted with each other to create safe machinery, he got into his truck and drove into Pittsburgh to photograph the kinetic reactions of punk rockers inside clubs and dive bars.

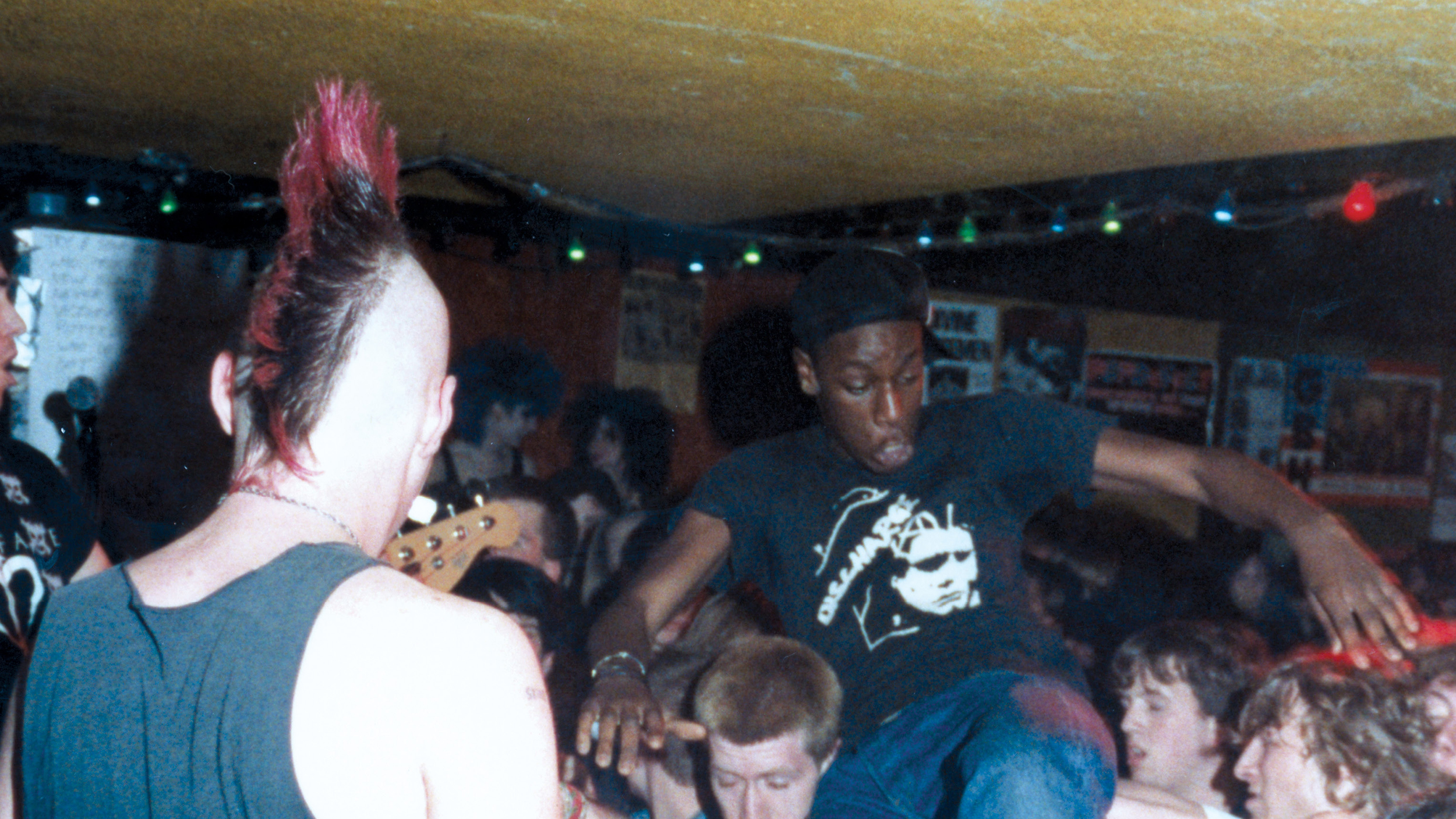

Those mouth-to-mic, fingers-to-guitar or body-to-crowd reactions aren’t quite the same as oxygen and hydrogen, but they too capture a chemistry. Erik’s photographs from that era appear in Mind Cure Records’ new publication, Had to Be There: A Visual History of the Explosive Pittsburgh Underground (1979 – 1994). Armed with his Nikon, Erik slipped into clubs like Electric Banana, a former disco dance spot turned punk house, and large venues like Syria Mosque, a 3,700-seat concert hall originally intended as a Masonic shrine.

“There was a place at the Westmore land Mall that did 24-hour film processing. When the show was over, I would go to those places and drop the film off that night and pick it up on the way home from work the next day,” Erik said to Mind Cure Records’ Mike Seamans in the introductory interview to the book.

Rinse and repeat — off to Kenna-metal in the morning and back into the city at night. When Mike asked Erik what motivated him to drive over the county line every night to document punk shows with “missionary zeal,” he shrugged it off with a simple answer, “It’s something I could do … I couldn’t be musical. I’m not artistic. But I could work a camera,” he said.

Erik has a knack for photographing movement. Glimmers and streaks of exposure use the low lighting of the venues to the photos’ advantage, almost like the spiritualist Victorian photography of poltergeists or auras. In one shot, The Usss and Mike Psyche look ghostlike — possessed by the music. In another, Valerie Barnes of The Imprints is manic with concentration as she cradles an electric guitar.

One of the ways to enjoy Had to be There is looking at the photographs and then flipping to the band index at the end for the anecdotes Erik and Mike included about each group. For example, The Imprints were from Greensburg, Erik’s stomping grounds in Westmoreland County, and made new-wave music with poppy hooks that got them “loathed” by Pittsburgh’s hardcore punk scene. The band then produced a song called “The Imprints Suck” to poke fun at their detractors.

Even if you know nobody in the book, small details give you a clue to their characters. Bob “Lex Luthor” Mullins of 99¢ wears a shirt with the Lacoste alligator on it that reads: “SAVE THE ALLIGATOR…EAT A PREPPIE,” as he bellows into a microphone. Drummer Mike LaVella of “scary AF, psychedelic, reptilian noise band” Moist boasts a t-shirt that just says: I Have Great Taste.

Duo Olivia Reed and Lita Wingertsahn overheard a comment at one show that “Blacks don’t swim” and founded the band The Beach Bunnies, where they arrived donning bikinis. Reed has extremely expressive eyes as she sings, clad in hot pink.

“Most of our songs were about sex, sexism, men and their dicks and how fucked-up America is,” Olivia explained to Mike. Some people hated them, some people liked them, but everybody — including Erik — remembered them.

Though musicians and critics squabble about whether filming on your phone at a concert is a faux pas, concert photography is still alive and well. But live music, particularly underground punk and hardcore shows, are experiences that resist documentation. You’re paying to sweat, dance and yell in a room with a bunch of strangers.

When you buy a ticket, you pay for the moment. You can watch a video of it or look at a photo, but as the title of the book says, at the end of the day, you had to be there. Much for the same reason novelists often flounder writing sex scenes, certain experiences rub up against our abilities to describe or capture them. Titling a book of concert photography Had to be There feels like something of a dare: How much can a photo make you feel like you’re in the scene? How do you document something that resists documentation?

For the record, I wasn’t there. I wasn’t even alive when Erik took these photos. The “scene” of Pittsburgh I know is a very different one. Erik’s book came out at the same time as Dave Rullo’s Gen X Pittsburgh, which documents the city’s bohemian culture that developed around The Beehive cafe in roughly the same time period as Had to be There. That era of the city is now a memory and many of the punk rockers and bohemians are now retirees and suburbanites. The Beehive, like Electric Banana and Syria Mosque, is now gone.

There’s a joke about Pittsburghers that they’ll give you directions based on where things used to be rather than what’s actually there, but to an extent, it’s true. Precious places get torn down and replaced with something that doesn’t tug at the heartstrings as much, especially in Rust Belt cities. It’s easy to reminisce about the way things used to be, and photography is one tool to take you back into those moments.

Taking photos of a “scene” elevates you, the people you know and the places you go into a canon. But why document things in this way? One answer is simply because by doing it, you turn those moments of sweating and yelling and partying with your friends, lovers and enemies into something worth documenting, that somebody other than you might care about. Whether it’s Fluxus, The Factory or the Beatniks, at one point, all famous “scenes” were just groups of people hanging out with each other and generating ideas.

As I read Had to be There, I kept coming back to a line from Michael Chabon’s Mysteries of Pittsburgh, one of the great tales of drama and debauchery in this small mountain city that’s pumped out music, literature and art alongside steel and chemical waste: “The people I loved were celebrities, surrounded by rumor and fanfare; the places I sat with them, movie lots and monuments.”

Work like what Erik Bauer and Dave Rullo are doing is what I could be doing in 10 or 20 years. That’s not self-importance on my part, because I could publish my documentation of the Pittsburgh art scene and it’s very possible that no one would care, but to me, it matters. And what comes through in Erik’s photography is that he saw the bands he captured as exciting and dynamic enough to remember 30 years later. Just as in chemistry, a reaction lasts only an instant, but its effects can be explosive.