You have never been a hunter. Our last one was sleek and thin, a velvet creature that weaved through the house like a shadow as he made his way to the back door and pawed at the glass until one of us let him outside. He brought gifts: birds, rats, squirrels. We left them at the doorstep, but we appreciated the thought.

Your presents are less violent. Your claws sink into my sweater instead of another animal’s skin, kneading until you’ve made a nest soft enough for your furry underbelly, and then you sit your rear end under my chin and brush your tail over my nose until I finally crane my head up to look at you. You are a dandelion puff, shedding fur like seeds in the wind. I have to spit to get your white hairs out from between my lips.

“You’re nasty,” I say as I pick litter from your fur. “Do you always go around sticking your poopy butt in everyone’s faces? Huh?” I scratch the top of your head and laugh at the trill you give me in response. It is the same trill you have given to my sister many times before, and now, she has entrusted it to me.

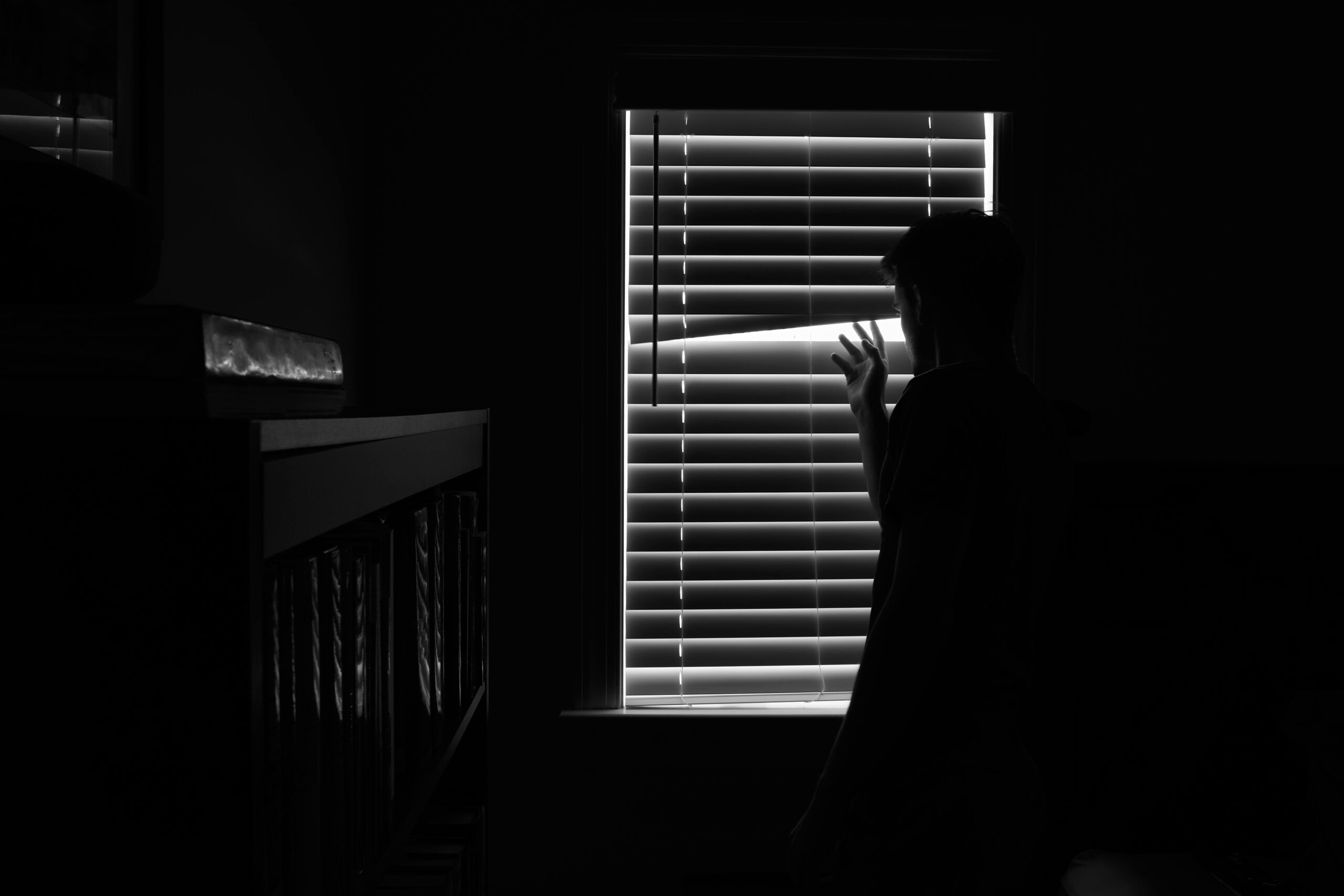

Dawn peers through the window blinds. I plop you onto my bed so I can stand and move the slots apart to look outside. It doesn’t seem like anything’s out there, save for the birds. The birds have always been there, crowding the landlines.

The crows are somewhat new, but I’ve gotten used to them.

I cradle you in my arms and carry you downstairs, passing the other bedrooms in the house. Your body molds to mine. I am thankful for the carpet silencing my footsteps, and I creak the basement door open and toss you down on the stairs, patting you when you look at me with big green eyes.

“Time for a grocery run, kitty. You be good while I’m gone.”

***

I have strict rules for going outside. I wear tennis shoes and socks that reach up to at least my ankles, tough denim jeans with no rips, and at least two layers on top no matter how hot it is. I always tie my hair up in a bun—I thought about shaving it off at first, but Mom convinced me not to, even though it’s more of a rat’s nest than anything else now. I still look both ways before crossing the street. And before I leave our property, I check that when I reach my right arm down to my hip, I can easily grab the rusted brown hilt of the Bowie in the holster attached to my belt.

The houses on our hill are nearly picked over by now. I crawl through the broken windows anyway, checking in corners of dusty garages and rotting basements and cobwebbed pantries for anything—I’m no longer picky like I used to be. I’ve learned to appreciate kidney beans as a good source of protein. Dried oatmeal, while good to have water (or milk, should luxury allow) to wash down with it, is enough some days as long as I eat slowly enough not to choke on the powder. Expiration dates on oils and spices are, at the end of the day, just suggestions. And it’s not like we’ve really been here long enough for them to make a difference.

This time, I find something special for you. The Williamsons’ old house, deceptively tiny and barren, houses a bag of cat food that is still three-quarters full. Their old, hacking furball passed away a year ago. Maybe the grief was too tender for them to throw it out before all of this started.

I hoist it onto my shoulder and can almost hear my little cousins, distant and gone away somewhere, calling me Santa. The coast is clear outside, so I waddle carefully with the bag and try not to shake it too much. I plop it onto our doorstep and take a deep breath, checking for my knife once more and venturing out to the houses I haven’t checked yet.

I’m fortunate enough to get three cups of sliced oranges, floating in juice under gleaming, unpierced plastic seals like some sort of aquatic specimen trapped in an isolated setting for observation. What a treat.

When I return to our house, I am able to drag your food inside to you—you are already digging your head in before I’ve shut the door behind you. “Patience, patience. I don’t want this place looking like a mess again.”

I retrieve the broom from the closet and dust it along the pebbles you’ve strewn onto the floor around you. I’ve finally found the motivation to clean the house when no one can see it except us.

***

The next day proves me wrong. In the early evening, as the sky turns to indigo, a knock comes at the door. You start to meow. I pick you up and shush you, freezing out of view of the front door. I can’t trust anything with the raiders coming around anymore.

“Anyone there?”

Well, they usually don’t ask.

I hold my breath and bounce you like a newborn baby. After another few knocks, it’s clear that he’s not going anywhere, so I let you down and take one small step after the other, hand cupped around my Bowie handle. But I don’t open the door or let him see me.

“I, ah… I saw the cat food? I live down the street? I thought you all were dead?”

My brow furrows. There’s something somewhat familiar about the lilt of the voice—he sounds like the Swigers’ son. I tighten my grip on the knife; I’ve never known him as a timid person, but as the kid my Dad opened his window to scold in the middle of the night when the dribbling of his basketball on his driveway wouldn’t grant us rest.

“I’ve been alone for a while? Uh… God, I’m talking to nothing right now, aren’t I. Ok, maybe you just don’t trust me, and that’s fine and all. I wouldn’t trust me either. Maybe I can like—” Clothes rustle beyond the door. “I have a chocolate bar. Open the door if you want it.”

I snort and immediately stifle it. Shit.

The air leaves the space between him and me. I purse my lips. You rub up against my legs and meow, long and loud, and I glare at you.

“… Ok. I’ll just leave this here. I’ll be back. Uh. Say hi to your cat for me.”

The patter of feet turns from concrete to grass until it eventually fades. I release all of the breath in my body at once and collapse against the door, pouting.

“You blew my cover.”

Wide-eyed, you turn away and waddle to your food bowl in the kitchen, as if to say, you didn’t need my help for that.

Deadly curious, I crack open the door and see a half-eaten Hershey’s bar in its wrapper, like an olive branch or a Trojan horse.

***

We’ve gone, eerily enough, in birth order.

Mom couldn’t handle it. Three weeks in, Dad had to hold me back from screaming when I came across her limp body dangling in the attic with a note begging God for forgiveness. Two months after that, we lost Dad when he tried to bandage our neighbor after a bandit raid and the thieves came back for more.

My sister—your mother—haunts my dreams every night. Sometimes I hear her calling me down for breakfast, half a scrambled egg for each of us and a few treats for you. Those are the hardest memories for me to relive—they are quickly swallowed by her groans echoing off of the walls and the sound her shoes made on the kitchen tile while she scavenged the refrigerator for the last time. I called her name and she turned to me, brown eyes underlined with thick indigo, her lips gnawed beyond her usual anxious habit of nibbling the inside of her cheeks. She was eating the raw steak we kept in the freezer that she wanted to save for a special occasion, back before even peanuts were too scarce to come by. But she threw it to the ground the moment she saw me, her arms outstretched. I said her name again and drew closer, reaching. She held me. I told her she was okay. Her breathing calmed and I tried to draw away, and at first I could not tell that it was her hold that tightened my neck against her chest. Her bitten nails broke the skin of my nape. I could hardly see straight when I was finally able to push her away.

I cried her name for the last time, but all I saw in her eyes was hunger.

She chased me around the island, and I yanked out drawers among the nonononono streaming from my mouth, feeling for something, anything, that I could use against her. She foamed; her moans forced strings of saliva out of her mouth, and they landed on my shirt. My throat was cracked dry by the time I pulled open the last drawer and wrapped my hand around a thick, wooden handle. As she shoved that same drawer closed to reach me, I wailed as I ran the cleaver across her neck, gasping apologies as her blood ran down her sweatshirt. She fell, groans cracking—I must’ve severed her vocal folds—and my own voice ripped itself from my body when I drove the knife into her temple, fogged snot dripping onto her face as I watched her last breaths evaporate. Her creaks melded into silence. I touched her cheeks, ran my fingers through her hair, wailed for her soul in hopes it could hear, and by the end of it all, I had smeared myself with her blood.

You pawed at the basement door, but I don’t know how long it took me to drag myself to it and let you up. You approached her, sniffing as if she wasn’t lifeless and blue. She was still warm. You licked her blood off my fingers and kissed her temple with your tongue. I nearly starved in the following days. I could not bring myself to go to the kitchen for anything at all.

I think she would be happy to know that she fed you for two weeks before I buried her with the rest of our family. I think she would be happy to know that the last traces of her didn’t fade from the fur around your mouth for another few days afterwards. And I think she would be happy to know that if I count the moment your last pink hairs turned back to white as the moment she actually died, she would have made it to her twenty-fifth birthday.

***

You find me nibbling on the last bits of chocolate in my room, shaking my hips as I sing Frankie Valli to myself.

“Do not give me that look. You never saw your mom do this? Hm?”

You plop on the floor and lick your forearm, dragging it over the top of your head in an attempt to clean it. All things considered, you haven’t done a bad job keeping yourself clean—my sister sometimes gave you baths using filtered water from the creek, although I am far too thirsty to afford you the same luxury. I wonder if I should try, if I’d even be able to get you underwater without the reward of scratches all up and down my arms.

I’m sad to swallow the final bite of Hershey’s. When I first tasted it, any suspicion I had towards the Swigers’ son left me in the form of tears and snot on a tissue. I cannot find the proper ingredients, nor do I know the proper technique to make Mom’s lasagna; nothing has tasted the same since she died. But chocolate is chocolate, and the sickly sweetness is the only thing I’ve had for a while that tastes like the before times. I recall the smell of firewood burning, marshmallows on a stick and s’mores smeared on cheeks, you fast asleep in your bed while we laughed outside without fear that it would attract undue attention.

“C’mon.” You freeze as I lick my fingers and reach for you, picking you up and holding you out like a lion cub in a Disney film. “Dance with me.”

I press you into my chest and hum the trumpets’ lead-in, shaking you to the beat of the drum. I love you, baby, and if it’s quite alright, I need you, baby, to warm the lonely night!

You are somewhat stubborn. I laugh as I catch your reflection in my mirror, wide-eyed but somehow trusting that I won’t drop you among the self-generated turbulence. I scratch your head and finish out with a kiss between your ears.

“Let me love you, baby, let me love you…”

***

He comes back in the rain, which might be romantic if we weren’t in an apocalypse. Instead, I’m left to contemplate how the boy who always rode through the neighborhood on a four-wheeler with a Swiss army knife in his pocket turned into a bundle of horrible survivalist decisions when it came time for him to actually put himself to the test. He knocks again to signal his arrival, and I sit against the front door to listen. You take advantage of this and plop yourself in my lap.

“Hope you liked the Hershey’s.”

This time, I snort freely.

“Don’t—don’t laugh at me!”

Unfortunately for him, this incites me even more and I burst into a giggling fit. Your purs jolt for a moment while I collect myself. “Don’t be funny, then,” I say.

“Oh, so you’re—that makes sense. That you’re the one left.”

My smile drops. “What does that mean?”

“Well, it’s hard to take care of a cat alone, right? And you haven’t really been all that subtle. I mean, you left the cat food out on your porch and that’s how I realized you were here in the first place.”

“I mean, I thought you died, so.”

“I thought you died.”

I sigh. “What are you here for?”

His fingers tap against the door. “I have a radio. And for a while, it wasn’t picking anything up, but…” I sit up. “I got something yesterday. The government’s been sending out… scouters, I guess, over different areas looking for survivors who are able to give them a signal.”

As his voice drags itself through the layer of wood behind me, I look at you curled up on my thighs, breath making your body rise and fall again and again. I think about the comfort of being taken in and cared for and not having to do it all myself, about not having to worry over my next meal.

“So what are you gonna do?”

Shuffle. “I have some firewood and matches,” he says. “I just wanted to let you know.”

I hear you yawn. You stir and stretch, peeling yourself off of my legs. I blink and stare at the ceiling, and after a moment of silence, I stand and open the door.

“Are you stupid?”

He’s taken aback, that’s for sure—whether it’s by my breathtaking end-of-days appearance or my question, I don’t know. His hair, once cropped short and close to his scalp, is grown out and greasy, flopping in his face. Like he styled it with the mud paving the incline of the hill across the street behind him. “What?”

“Anyone could see that smoke signal. Sure, maybe it’ll be the government. Maybe it’ll be raiders and we’ll all die because you wanted to let them know there are still living people to ransack.” I feel you rubbing against my legs. His gaze drifts down to you, and despite the words leaving my mouth, I see his eyes soften when you look at him and your pink nose twitches. “Don’t you remember what they did to your dad? To mine?”

His lips scrunch. “Yeah, I do. And I thought about it. And I don’t think I have another choice.” He bends down to pet you, but you pull your head away. He sighs. “I’m setting fire to my heap tomorrow, so do whatever you need to do in the meantime. But don’t say I never tried to help you.”

A breeze flies into the room, and I shiver. I notice in my periphery that a scarce ring of red leaves surrounds the dogwood tree in his front yard. He blinks at me, and I do the same in return until his nose scrunches. He wets his lips with his tongue and I wonder if whatever thought is making his face wrinkle like that is about to come out of his mouth.

“I remember what they did to my dad and I remember why yours died too. Why else do you think I’m telling you any of this?”

And with that, he brushes his hair out of his face and leaves. I groan as I shut the door.

“What a charmer.”

You trill in agreement.

The smoke signal goes up the next morning. I pack what little I can. We’ll have to leave either way.

***

Long before we had you in the house, when I was much smaller and didn’t have to worry about keeping myself—much less another being—alive, my dad and sister tried to teach me to shoot a BB gun. Dad carved out styrofoam circles and drew crude bullseyes on them in red Sharpie, and then he set them against the bases of the trees in our backyard before handing the gun to my sister and standing behind her to help her position it.

“Perfect,” he said as the pellet sank in the outermost ring of red. I covered my ears every time my sister pulled the trigger, and I crunched the leaves under my boots to try to muffle the sound. It didn’t help.

After a few minutes, my dad turned to me. “You try.”

The trigger was warm from my sister’s touch. I kept the gun aimed towards the ground—Dad had said never to point it at anyone while it was loaded. My arm was stiff beneath my puffer jacket as I held the gun out towards the target.

“Relax your arm and shoulder. Take a deep breath. Be ready for the recoil.”

I screamed when I pulled the trigger, which made my dad and sister laugh.

“See? You didn’t hurt anyone. Look.” Dad pointed at the target, where the center circle was pinpointed cleanly in the middle by my shot. “You did awesome!”

My sister patted my shoulder, her palm settling atop the buoyant, airy fabric keeping me warm. “Good job!”

I nodded, pointing the gun at the ground again.

“Let’s do one more?” Dad asked with a smile.

I shook my head. “That was scary. I don’t wanna hurt anyone.”

His eyebrow furrowed, but he took the gun back from me and gave it to my sister again. I crouched against our house and breathed slowly, crunching dried leaves into dust. The styrofoam targets were obliterated within the hour, and when we went inside, my dad and sister held my hands extra tightly.

Don’t worry. We’ll always protect you.

***

“Come on, please, please, please, we don’t have time for this!”

I urge you out of the house, my arms bleeding and scratched nearly raw by you. But you yowl and retrieve back into what you know to be safe despite the distant thunder of something coming. My face is red and dried from salt, and as I lunge for you once more, you dash further into the house, up the stairs, curling around the bend in the hallway that leads to my bedroom.

Suddenly, the backpack on my shoulders nearly causes me to collapse. I stumble in behind you and swing the door shut, dropping the weight I carry to the ground and crawling my way up the steps to you.

“We have to go.”

But then I reach my room, and I see you standing on the covers and waiting for me, biscuiting a body that isn’t there. And I think of the half-mangled bodies shoddily buried in the backyard, family pried from my hands without closure. And I ache, and you stare, and the thunder grows louder, and your meowing pulls me closer to the bed.

I’m so tired.

When I crawl under the covers and you lay on top of me and the thunder reaches the front door, I realize that I probably won’t be able to rest with my family, but it’s ok, because at least I have you. I try to hum myself to sleep as I stroke your belly.

You have never been a hunter, but then again, neither have I.